This week, on the 26th March 2019, the European Parliament approved the controversial EU Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market [“the Directive”] which will now pass on to the European Council for final approval by Member States. Should the amended text of the Directive be adopted, Member States will have 2 years from publication to implement it.

Objectives of the EU Directive on Copyright

This Directive, which does not create any new rights for creatives but provides for better enforcement of their rights in the digital sphere, aims:

- to modernize the EU Copyright Framework to take account of the evolution of digital technologies and the way copyright-protected works are accessed and shared across borders over the internet in the internal market;

- to enhance rightsholders’ (e.g. musicians, performers, authors, news publishers) rights and chances of better remuneration when their works are distributed over various internet platforms like YouTube, Facebook and Google News;

- to make it easier for copyright works to be used freely for text and data mining to boost European research as well as when the content is used for teaching purposes;

- to allow the use of copyright content to be used free of charge for the preservation of cultural heritage;

- to introduce measures for better licensing practices and ensure wider access to content in regard to out-of-commerce works and audio-visual works on video-on-demand platforms;

- to provide harmonized protection to press publications in respect of digital uses at EU level by defining the term press publication and the right granted to publishers of press publications under the Directive;

- to increase collaboration between rightsholders and the information society service providers who store and provide access to the public to large amounts of copyright-protected works for the better functioning of technologies such as content recognition technologies; and

- to provide fair remuneration in contracts of authors and performers through transparency obligations, appropriate remuneration adjustment mechanism and alternative dispute resolution procedures in cases of dispute.

The Controversy

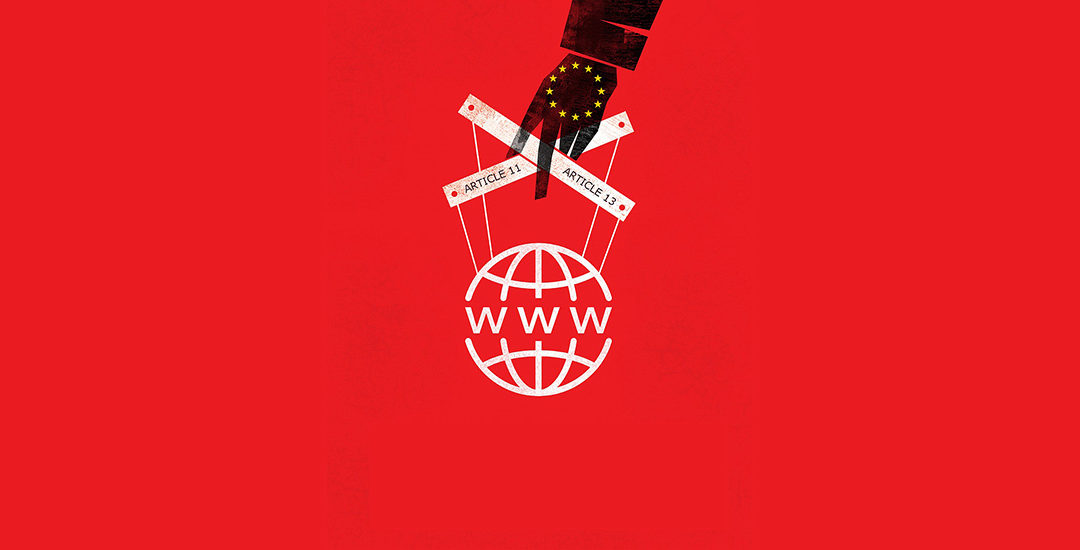

The controversy arose between, on the one hand, EU lawmakers who wanted to correct the imbalance in remuneration between tech giants and all content creators, musicians and authors who deserved fairer compensation for their copyrighted works which were being exploited online, and, on the other hand, big tech companies who argued that the vague law was making them liable for all infringing content uploaded on their sites and internet activists who warned against restrictions in online information.

Social media platforms claim that they do not have the means of combing through all uploaded content for infringing material and they will be forced to create filters that will block anything suspicious. Moreover, the ‘link tax’ which big tech companies are being obliged to pay in terms of shared revenue with publishers will lead to websites reducing published content and users finding it harder to access information.

The (in)Famous #Article 13

The original text of Article 13 (newly amended Article 17) which holds tech companies responsible for all uploaded content on their sites including those without copyright license created fears over the future of ‘memes’ and ‘GIFs’ which would be blocked by new add on filters blocking infringing content. In a world of daily digital ‘liking’ and ‘sharing’ and the creation of funny ‘memes’ and ‘GIFs’, the idea that no one would be able to freely share any online content without getting into an infringement dispute with a rightsholder led to an online tweeting storm advocating against #Article13 and #saveyourinternet.

Approved EP text

The final text approved by the European Parliament claims to bridge the controversy by upholding the initial objective of giving fairer remuneration to authors, musicians and content creators whose work is exploited digitally whilst “guarantee(ing) that the internet remains a space for free expression” by exempting ‘memes’, ‘GIFs’ and ‘snippets’ and distinguishing between upcoming innovative start-ups and big tech companies profiting from the current system.

Despite the best efforts of the European Parliament to tackle everyone’s concerns, time will tell how the final directive will be implemented and interpreted across borders and its impact on internet freedom.

For further information on Copyright or Intellectual Property, kindly contact Dr Sarah Galea or any other member of IURIS Advocates.